Photo taken on Dec. 10, 2005 in Stockholm, Sweden shows Professor Barry Marshall (L) and Robin Warren presenting their Nobel Prizes for Physiology or Medicine. (Photo credit: University of Western Australia)

"In China these days, at least in medical audiences, most people can speak quite a bit of English, and follow a lecture with good PowerPoint slides. Similarly, I can go to a lecture and see the slides in Mandarin and can usually figure it out. Science, to some extent, is a universal language, I suppose," said Australian Nobel Prize winner Professor Barry Marshall.

SYDNEY, Sept. 28 (Xinhua) -- Australian Nobel Prize winner Professor Barry Marshall's innate curiosity has set him on an unpredictable, occasionally risky but always fascinating journey through life.

His enquiring mind has taken him from his boyhood in the outback Western Australian city of Kalgoorlie in the 1950s to the professorship of the School of Biomedical Sciences at the University of Western Australia (UWA).

Along the way there have been plenty of personal and professional detours including dozens of trips in China since the early 1990s.

One of his earliest visits was to Guilin, where the surreally enchanting scenery piqued the esteemed gastroenterologist's deep interest in China, its culture and language.

Photo taken on Dec. 10, 2005 in Stockholm, Sweden shows Professor Barry Marshall (L) receiving the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine. (Photo credit: University of Western Australia)

It has led Marshall to determinedly study Mandarin for about a decade and although admitting being a "poor student" too busy to do his homework, he enjoys the analytical aspects of the language.

"The key to Mandarin is the vocabulary. It is like algebra or mathematics, so it makes a lot of sense," Marshall said, speculating that the cognitive process innately developed to be a native Mandarin speaker may help many Chinese also be capable mathematicians.

"I think the secret to learning it is to be in the environment and speak it," he said. "I'm at the stage where I think a couple of months in China among Chinese people not talking in English would really consolidate it for me. Just get in there and do it."

Marshall's delving into the deep end approach to life can also be seen in the role he played in shedding light on an ailment that inflicts millions worldwide.

Peptic ulcers are excruciatingly painful open sores or holes in the stomach lining or intestines that can lead to fatal internal bleeding and be a precursor to stomach cancer.

Conventional medical wisdom in the early 1980s was that it was largely due to genetic vulnerabilities or lifestyle factors such as dealing with excess stress or indulging in too many spicy meals.

Marshall and his research partner Dr. Robin Warren, however, were reaching other conclusions with their experiments showing that an extremely common bacteria, helicobacter pylori, was a main culprit.

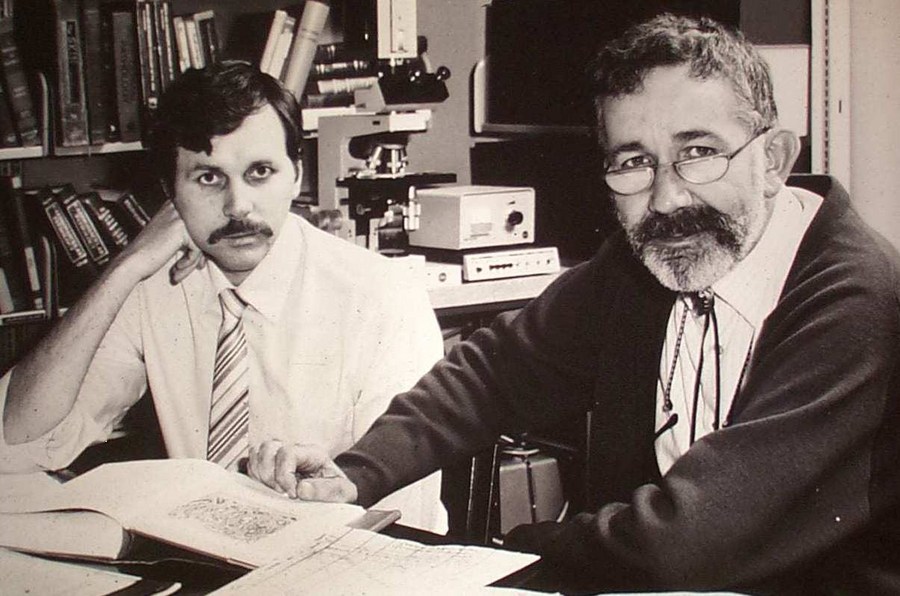

File Photo shows Professor Barry Marshall (L) and Robin Warren pose for photo with their findings in 1984. (Photo credit: University of Western Australia)

Their work, however, was met with indifference or disbelief by the scientific community which demanded proof of their theory. They needed to show the effects of the bacteria on an otherwise healthy person.

It was, however, impossible to infect animals with a human specific pathogen and unethical to deliberately get someone healthy to ingest bacteria.

So, the headstrong Marshall took matters into his own hands one day in 1984 by making a broth brimming with the gut bug and, without even his wife's knowledge, quaffing it down.

The effects were dramatic, to say the least.

"A few days after that, my mother and my wife were complaining about my bad breath," Marshall said. "Then all my laboratory friends moved to the lab next door. And then I started vomiting."

Sure enough, Marshall had the hallmarks of someone developing peptic ulcers, which, fortunately, were then tamed by a dose of antibiotics.

The stomach-turning experiment has gone on to improve millions of lives and ultimately earned Marshall and Warren the Nobel Prize in 2005.

Although Marshall describes winning the prestigious award as being "like a dream" and joking that he is "definitely not giving it back", there are much more satisfying aspects of his medical career.

"I say to people in science, that the most exciting part is knowing that you've discovered something new that maybe is going to benefit mankind," he said.

"Your whole life becomes very, very interesting when you make a scientific discovery and that is bigger than just the Nobel Prize."

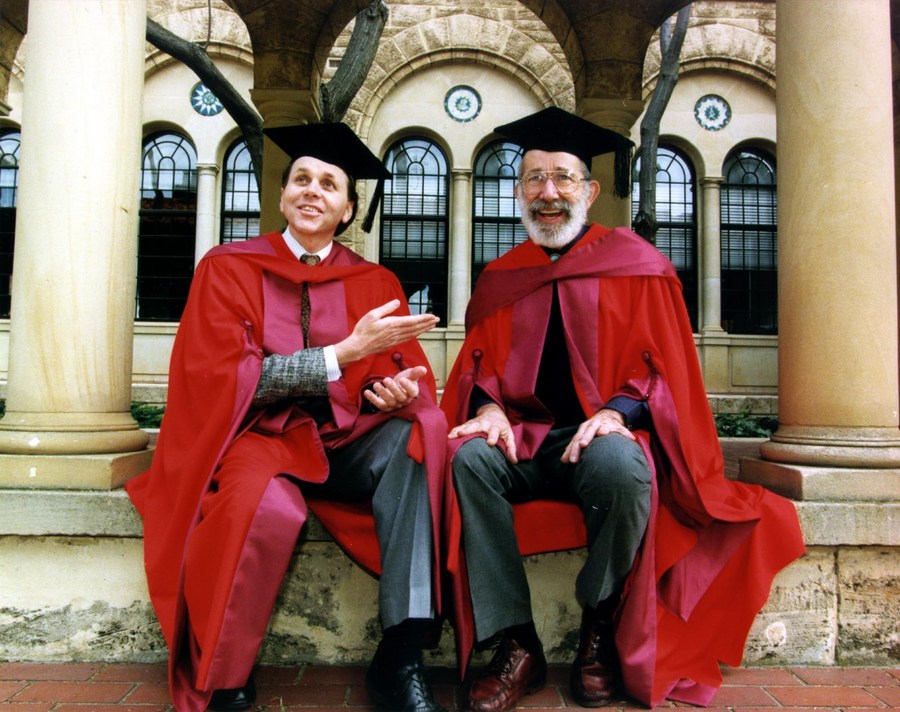

File photo shows Nobel Prize winners Professors Barry Marshall (left) and Robin Warren in their University of Western Australia professorial gowns.(Photo credit: University of Western Australia)

Now on the cusp of his 70th birthday, the energetic grandfather remains keenly interested in sharing his hard-won knowledge in science and languages.

"Typically, when I go to China, I'll give a couple of lectures," Marshall said. "And then I might have a few days running clinics in Shanghai or Shenzhen, Guangzhou," cities among the biggest in China.

"In China these days, at least in medical audiences, most people can speak quite a bit of English, and follow a lecture with good PowerPoint slides. Similarly, I can go to a lecture and see the slides in Mandarin and can usually figure it out. Science, to some extent, is a universal language, I suppose."

Marshall is also pleased his health message has been well-received there.

"I've got to hand it to the Chinese health system. Their government has really embraced the helicobacter treatment," he said.

"Many people that I have met there have been tested and treated for it. By combining a blood test and a breath test, you can have a very, very accurate diagnosis of helicobacter."

That is ample reward for the good doctor. ■